arsons and demolition at the Heidelberg Project |

date |

site of demolition and/or arson |

parties responsible |

8 December 2013 |

Clock House |

unknown |

28 November 2013 |

The War Room |

unknown |

21 November 2013 |

Penny House |

unknown |

12 November 2013 |

House of Soul |

unknown |

3 May 2013 |

Obstruction of Justice House (OJ House) |

unknown |

1998 - 1999 |

building titles n/a |

Mayor Dennis Archer |

November 1991 |

3 - 4 buildings |

Mayor Coleman A. Young |

Performance transforms a constant into the per-formative, whereby the identity of actors becomes blurred. The simultaneity of events becomes distinct via performance. As a performance, the city of Detroit including Tyree Guyton and Sam Mackey (both of whom founded the Heidelberg Project in 1986), East Side residents, city officials and non-profits participate in determining the aesthetics of the Heidelberg Project (figs. 1 & 2), which, in turn, determines the (re)presentation of the city. As a performance, the Heidelberg Project intersects politics and aesthetics by bringing art closer to life and vice versa.

| figures 1 and 2 |

|

|

Tyree Guyton

The Heidelberg Project, 1986 –

photos courtesy stephen garrett dewyer |

If the Heidelberg Project is a performance, it becomes distinct from just its institutionalization as an open-air museum that seeks to build a legacy. As a performance, the Heidelberg Project has a particular duration and, thus, differs from attempts to turn the Heidelberg into a constant site of maintenance. Although the destruction of the Heidelberg shows the disdain of city officials and, perhaps, unknown parties for the everyday lives of constituents in the East Side of Detroit, it also demonstrates the partial agency of East Side inhabitants to determine the aesthetics of their neighborhood. While not dismissing the (de)valorization of art, the destruction and re-building of the Heidelberg Project shows some of the problems that arise when art loses sight of its performance.

Despite the local, national and transnational critical acclaim the Heidelberg Project received, two different mayoral administrations and unknown parties sought its destruction. The official and unofficial arson and demolition of much of the Heidelberg Project shows the necessity for conversations about art + life to happen in order to attempt to translate the passions around politics via aesthetics and, thus, question the sensibilities behind (re)presentation.

Whereas the performance of the Heidelberg Project shares similar aesthetics to art practices such as those of Krzysztof Wodiczko, Gordon Matta-Clark and Michael Rakowitz in its use of city architecture to open spaces for public participation, it also resembles the work of many artists in Detroit who often use the city for their work and whose work faced imminent destruction. Design 99 (figs. 3 & 4), Powerhouse Productions, Katherine Craig and the many graffiti artists are some of the collaborations and artists whose work Detroit features predominantly. While the aforementioned artists share similar stakes in the effacement of art and its public, the Heidelberg Project has a particular role in defining the nature of city involvement in public art in Detroit.

| figures 3 and 4 |

|

|

Design 99 (Mitch Cope and Gina Reichert) and Wiley McDowell

The Talking Fence & Illuminated Garage, 2012

15378 Lamphere Street, Brightmoor, Michigan

photos courtesy stephen garrett dewyer |

Within numerous interviews and articles about the Heidelberg Project, the work is positioned as Outsider Art. The term Outsider Art, however, seems not to encompass the scope of the Heidelberg nor its position in Detroit. Tyree Guyton received critical acclaim and numerous awards including the Spirit of Detroit Award (1989), a solo exhibition at the Detroit Institute of Arts (1990), Governor Artist of the Year Award (1992), a $47,500 grant from the City of Detroit (1997), a Kresge Fellowship (2009), a Wayne State University 2009 Community Leadership Award (2010) and has been the subject of a documentary called “Art from the Ashes: Detroit’s Heidelberg Project” (2010). A 2013 exhibition of Guyton’s work at the CUE Foundation suggests calling the Heidelberg’s work that of an “outsider” a misnomer.

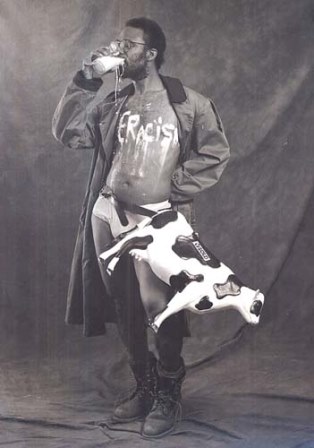

Multiple conceptual practices seem to play in the Heidelberg Project. Formally, the work shares similarities to that of artists such as Noel Anderson (figs. 5 & 6), William Pope L. (fig. 7) and Jean-Michel Basquiat (fig. 8). Tropes of African-American history, civil rights, the Holocaust, unemployment and sexuality evoke through sculptures and installations made of found shoes, dolls, tires, stuffed animals and appliances among other things. In an article about the pending destruction of the Heidelberg in 1998, Galen writes “[a] display of old shoes' soles was inspired by Guyton's grandfather's recollections of lynchings in the South… shoes lining the sidewalk represents those standing in unemployment lines; an oven, the suffering of those who died in the Holocaust” (Galen. “The last days of the Heidelberg Project: Detroit authorities force dismantling of art work.” http://www.wsws.org/en/articles/1998/08/guy-a20.html). Galen continues, “[Guyton] has painted houses, trees, and abandoned buildings with colorful polka dots to represent the unity of people of all color” (ibid.). Guyton’s practice takes common objects left scattered among abandoned and neglected neighborhoods in Detroit and arranges them en masse to attempt to show the historicity within the tropes evoked by specific objects.

| figure 5 |

|

Noel Anderson

2010 Yale Sculpture M.F.A. Thesis Exhibition, 2010

photo courtesy Sandra Burns |

figure 6

|

|

Noel Anderson

Mascuminity, Ch. 26: He's a Magik Men, 5 September - 23 October 2013

photo courtesy Jack Tilton Gallery |

figure 7

|

|

William Pope L.

Friends in NY - William Pope.L

Performance at the Whitney Museum of American Art in conjunction with the exhibition Blues for Smoke

date n/a |

figure 8

|

|

Jean-Michel Basquiat

Six Crimee, 1982

Acrylic and oil stick on masonite

72 x 144 in.

The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles

The Scott D. F. Spiegel Collection |

While the Heidelberg Project seems, in part, an extension of the City Beautiful Movement (fig. 9), it also seems part fluxus-inspired happening. Whereas the City Beautiful Movement sought to “promote a harmonious social order that would increase the quality of life” (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/City_Beautiful_movement) in cities where industrialization produced slums, the Heidelberg seeks to “inspire people to appreciate and use artistic expression to enrich their lives and to improve the social and economic health of their greater community” (http://www.heidelberg.org/who_we_are/mission.html). Whereas the City Beautiful Movement sought to increase the quality of life in dense urban areas by imposing a sense of civic virtuosity,1 the Heidelberg seeks to improve the quality of life through empowering communities to see art in their everyday. The latter resembles fluxus in its attempt to bring art closer to life, but turns towards the City Beautiful Movement in its claims to have an effect such as empowerment.

| figure 9 |

|

Cass Gilbert

James Scott Memorial Fountain

Belle Isle, Detroit, Michigan

photo courtesy stephen garrett dewyer

|

|

Tyree Guyton

The Heidelber Project, 1986 –

photo courtesy stephen garrett dewyer |

The Heidelberg’s role in providing solutions and healing through art seems unknown. With a median household income of $22,451, 43.2% of individuals living below poverty level, an unemployment rate of 13.8% and a Bachelor’s degree attainment rate of 9.3% for individuals 25 years and older according to the 2010 U.S. Census, the 48207 zip code (fig. 10) that the Heidelberg shares seems to suffer from a deep economic depression. When asked about how the neighborhood has changed since the founding of the Heidelberg, Heidelberg Executive Director Jenenne Whitfield responds: “[i]t’s been on a constant decline. I think our work has served to bring relevance to many Detroit neighborhoods that have been written off. Our work has already served as an economic catalyst” (dewyer. Interview with Jenenne Whitfield. 24 December 2013). With the East Side of Detroit in steady economic decline, the Heidelberg’s role as an economic catalyst seems uncertain.

| figure 10 |

|

48207 zip code reference map

image courtesy 2010 U.S. Census |

As a fluxus-inspired happening, the Heidelberg Project seems to serve a critical role in making visible the dissonance between the Detroit City Council, Mayor’s Office, residents of the East Side of Detroit and the art community. Coleman A. Young bulldozed four Heidelberg buildings in November of 1991 as mayor after Guyton appeared on the Oprah Winfrey Show. Although the then mayor regarded the Heidelberg Project as a pile of trash,2 the Heidelberg’s drawing attention from outside of Detroit to the city’s blight and neglect very likely disagreed with maintaining the status quo by city representatives. Most of Guyton’s work, writes Whitfield:

is a commentary on everyday life. For example, one element of the canvas is a podium with shoes stuffed inside and a cash register resting on top. That work is called, “Big Business”… [and represents] the vast amount of churches in the city vs. schools. It’s provocative in that it asks questions on what’s really happening in these so-called holy sanctuaries and why our communities look the way they do. The burial of the Pink Hummer speak to the greed and consumption of the auto industry. There are also many playful themes like Noah’s Ark. In other words, it’s like the HP sign reads, “The HP is saying, seeing and feeling all things.” (Ibid.)

Guyton, while calling attention to the blight in Detroit, also makes visible the difference between the everyday life of residents on the East Side of Detroit and the maintenance of power within city governance. Such disagreement very likely led to the 1998 – 1999 dismantling of some of the Heidelberg by the then mayor Dennis Archer, who sought to make Detroit business-friendly.

Paradoxically, the blight and neglect that made the Heidelberg possible also provided the reason for its partial destruction. Coleman Young and Dennis Archer’s failure to answer why the Heidelberg Project deserved demolition and not the approximately 40,000 abandoned and neglected buildings throughout Detroit foregrounded the performativity of the Heidelberg and the intolerance of city representatives towards art that challenged their authority. In covering the demolition of the Heidelberg in 1999, Ryan Moore writes “[t]he Heidelberg Project has been bashed by city officials as an eyesore that wouldn’t have lasted a second had it been moved to the suburbs. But the suburbs don’t need to draw attention to the urban plight. That was Tyree Guyton’s point. In changing the neighborhood, he was trying to change the world, one person at a time” (Moore. p. 55). While the change affected by the Heidelberg remains unclear, its destruction means one less blighted property in Detroit as well as a loss of art for the city. The Heidelberg’s ability to transform blight into art, however, becomes an empowering mechanism for impoverished communities to see beauty in the everyday. If viewed as a performance, the Heidelberg’s loss of holdings would not detract from its meaning, which is rooted in the potential of city inhabitants to bring art closer to life and vice versa.

I visited the Heidelberg after the Penny House burned to the ground last November. The manicured lawns and clean streets seemed to distinguish the Heidelberg from the surrounding area. The Heidelberg’s role as an open-air museum, a different iteration than its guerilla days during the 80’s and 90’s, shows some similarities to a park. That anyone may visit the Heidelberg poses a radical disjunction from the institutionalization of museum hours and fees. However, the preservation of the Heidelberg as a museum turns the Heidelberg into a monument. As a monument, the Heidelberg becomes removed from the intersection of art and life. The focus on securing a legacy comes at a cost of losing participation from the city in determining the Heidelberg’s aesthetics.

The destruction of the Heidelberg seemed poetic (figs. 11 - 13). The work about blight and neglect in Detroit led to a few less blighted properties. Unintentionally, the work drew the city to respond to art it could not tolerate however ordinary and ubiquitous to inhabitants it might appear. The destruction showed the farce of the city officials who claimed to represent the city of Detroit but saw work about their everyday lives an eyesore. While such iteration may not promise solutions, the questions are critical for re-imagining the role of (re)presentation in communities largely abandoned and neglected by global capital.

| figures 11 - 13 |

|

|

|

Tyree Guyton

The Heidelberg Project, 1986 -

photos courtesy stephen garrett dewyer

|

1 Jane Jacobs criticized the City Beautiful Movement as an “architectural design cult” in The Death and Life of Great American Cities (New York: Random House, 1961), p.375; quoted in Rybczynski, Witold. City Life: Urban Expectations in a New World. New York: Scribner, 1995:.p.27.

2 “Part of the problem that has plagued the Heidelberg Project since its inception is its perception by many as a pile of trash” (Moore. “Tyree Guyton Demolition Man: Picking up the Pieces after the Fall of Detroit’s Heidelberg Project.” p. 55).

works cited

Battaglia, Tammy Stables. “Artists to march in support of Heidelberg Project.” Detroit Free Press. 19 December 2013.

Battaglia, Tammy Stables. “Fire destroys another Heidelberg house; federal ATF agents join arson probe.” Detroit Free Press. 21 November 2013.

dewyer, stephen garrett. Interview with Jenenne Whitfield. Interview conducted by email. 24 December 2013.

Galen, E. “The last days of the Heidelberg Project: Detroit authorities force dismantling of art work.” World Socialist Web Site. 20 August 1998.

Garza, Ryan. “Fire at the House of Soul house at the Heidelberg Project.” Detroit Free Press. 13 November 2013.

Heidelber Project.

Jones, Shannon. “Protest turns back attempt to demolish art project.” World Socialist Web Site. 23 September 1998.

Moore, Ryan. “Tyree Guyton Demolition Man: Picking up the Pieces after the Fall of Detroit’s Heidelberg Project.” Juxtapoz Magazine. May/June 1999: number 20.

Nasar, Jack and David Moffat. “Tyree Guyton: The Heidelberg Project – Detroit, Michigan.”

Neavling, Steve. “Brazen arsonist strikes 5th Heidelberg Project house in 2 months.” Motor City Muckraker. 8 December 2013.

Neavling, Steve. “Thanksgiving blaze destroys 4th Heidelberg Project house in 2 months.” Motor City Muckraker. 28 November 2013.

Neavling, Steve. “The sad demise of the Heidelberg Project’s ‘Clock House’ (photos).” Motor City Muckraker. 11 December 2013.

Stryker, Mark. “Fire claims part of Heidelberg Project, but the art, like Detroit, will survive.” Detroit Free Press. 4 May 2013.

Wikipedia. “City Beautiful Movement.”

|